Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL)#

In the chapter of propositional logic we have seen the combinatorial explosion problem that results from the need to include in the reasoning / inference step all possible states and actions combinations over time (the KB was growing substantially over time).

To avoid such explosion, with obvious benefits to the planning efficiency, we

Introduce a factored representation language called Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL) that allows for compressive expressiveness of the planning domain (general application space such as logistics) and problem (the specific logistics task we face).

Solve the planning problem by using domain-independent solvers that are able to reason over the PDDL expressed domain and problem. The domain independence is probably not the most efficient way to solve a planning problem but it is the most general and flexible way to do so and the associated tradeoff is worth making.

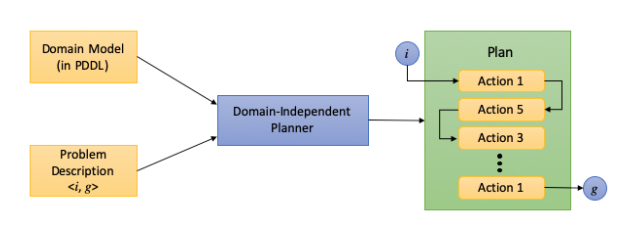

As show in the figure below, a domain-independent solver or planner takes two inputs: 1) the domain model written in a planning language and in the so called domain file and 2) a problem definition that describes the initial state \(i\) and the desired goal state \(g\) using the domain model’s terminology; and produces as output a plan, that is, a sequence of actions that takes the agent from the initial state to the goal state.

Automated Planning System (from here)

Automated Planning System (from here)

PDDL Language Constructs#

PDDL Domain File#

PDDL expresses the four things we need to plan a sequence of actions. The set of all predicates and action schemas are defined in the domain file (\(\mathtt{domain.pddl}\)) as shown next.

Domain Syntax |

Description |

|---|---|

Types |

A description of the possible types of objects in the world. A type can inherit from another type. |

Constants |

The set of constants, which are objects which appear in all problem instances of this domain. |

Predicates |

A predicate is the part of a sentence or clause containing a verb and stating something about the subject. Each predicate is described by a name and a signature, consisting of an ordered list of types. Properties of the objects (contained in the problem specification) we are interested in. Each property evaluates to TRUE or FALSE. The domain also describes a set of derived predicates, which are predicates associated with a logical expression. The value of each derived predicate is computed automatically by evaluating the logical expression associated with it. |

Actions / Operators |

Actions are described by action schemas that effectively define the functions needed to do problem-solving search. The schema consist of the name, the signature or the list of all the boolean variables that are ground and functionless, a precondition and effect. The signature is now an ordered list of named parameters, each with a type. |

The precondition is a logical formula, whose basic building blocks are the above mentioned predicates, combined using the standard first-order logic logical connectives. The predicates can only be parametrized by the operator parameters, the domain constraints, or, if they appear within the scope of a forall or exists statement, by the variable introduced by the quantifier. |

|

The effect is similar, except that it described a partial assignment, rather than a formula, and thus can not contain any disjunctions. |

|

In PDDL a state is a conjunction of ground boolean predicates which means that if the predicate has any arguments they are constants (grounded) without any variables. For example, $\(\mathtt{On(Box_1, Table_2) \land On(Box_2, Table_2)}\)\( is a state expression. \)\mathtt{Box_1}\( is distinct than \)\mathtt{Box_2}$. All fluents that are not specified are assumed to be FALSE - the so-called closed world assumption. |

Note that the specification via action schemas rather than via an enumeration of all possible actions for all possible states is compressive via the usage of variables.

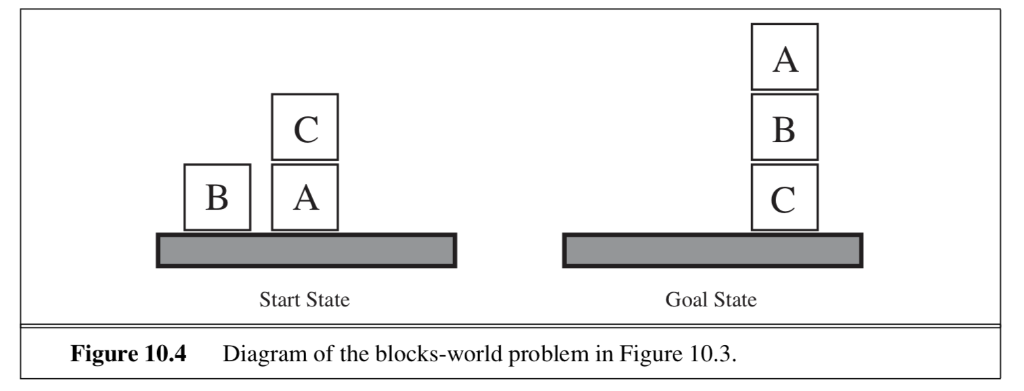

For the famous Blocksworld domain shown below where a robotic arm must reason to stack blocks according what the goal is, we list the corresponding domain PDDL specification.

Blocks planning problem

Blocks planning problem

In natural language, the rules are:

Blocks are picked up and put down by the arm

Blocks can be picked up only if they are clear, i.e., without any block on top

The arm can pick up a block only if the arm is empty, i.e., if it is not holding another block, i.e., the arm can be pick up only one block at a time

The arm can put down blocks on blocks or on the table

Noteworthy is that these rules can be automatically translated into PDDL via ad-hoc or via foundational Large Language Models (LLMs).

In PDDL these rules are expressed as:

;; This is the 4-action blocks world domain which does

not refer to a table object and distinguishes actions for

moving blocks to-from blocks and moving blocks to-from table

(define (domain blocksworld)

(:requirements :typing :fluents

:negative-preconditions)

(:types block) ; we do not need a table type as we use a

special ontable predicate

(:predicates

(on ?a ?b - block)

(clear ?a - block)

(holding ?a - block)

(handempty)

(ontable ?x - block)

)

(:action pickup ; this action is only for picking from table

:parameters (?x - block)

:precondition (and (ontable ?x)

(handempty)

(clear ?x)

)

:effect (and (holding ?x)

(not (handempty))

(not (clear ?x))

(not (ontable ?x))

)

)

(:action unstack ; only suitable for picking from block

:parameters (?x ?y - block)

:precondition (and (on ?x ?y)

(handempty)

(clear ?x)

)

:effect (and (holding ?x)

(not (handempty))

(not (clear ?x))

(clear ?y)

(not (on ?x ?y))

)

)

(:action putdown

:parameters (?x - block)

:precondition (and (holding ?x)

)

:effect (and (ontable ?x)

(not (holding ?x))

(handempty)

(clear ?x)

)

)

(:action stack

:parameters (?x ?y - block)

:precondition (and (holding ?x)

(clear ?y)

)

:effect (and (on ?x ?y)

(not (holding ?x))

(handempty)

(not (clear ?y))

(clear ?x)

)

)

)

The objects, the initial state and the goal specifications are defined in the problem file (\(\mathtt{problem.pddl}\)) as shown next.

Problem Syntax |

Description |

|---|---|

Initial State |

Each state is represented as conjunction of ground boolean variables. For example, $\(\mathtt{On(Box_1, Table_2) \land On(Box_2, Table_2)}\)\( is a state expression. \)\mathtt{Box_1}\( is distinct than \)\mathtt{Box_2}$. All fluents that are not specified are assumed to be FALSE. |

Goal |

All things we want to be TRUE. The goal is like a precondition - a conjunction of literals that may contain variables. |

(define (problem BLOCKS-11-0)

(:domain BLOCKS)

(:objects F A K H G E D I C J B )

(:INIT (CLEAR B) (CLEAR J) (CLEAR C) (ONTABLE I) (ONTABLE D) (ONTABLE E)

(ON B G) (ON G H) (ON H K) (ON K A) (ON A F) (ON F I) (ON J D) (ON C E)

(HANDEMPTY))

(:goal (AND (ON A J) (ON J D) (ON D B) (ON B H) (ON H K) (ON K I) (ON I F)

(ON F E) (ON E G) (ON G C)))

)

PDDL Tools#

Use the PDDL VSCode extension as described here

to invoke this planning server and ensure you understand the ropes of using PDDL planners. The blocks word problem is a classic problem employed in the International Planning Competition (IPC) 2000. For non-trivial examples in robotics see Plansys2 - any AI engineer must know and understand the ROS2 platform.

PDDL Solvers (Planners)#

Now we need to look how the planners solve the PDDL expressed problems. As it turns out many use the Forward (state-space) Search algorithms where despite the factored representation assumed here, we can treat states and actions as atomic and use forward search algorithms with heuristics such as A*.

The Fast Downward planner is a state-of-the-art planner that uses the FF heuristic and the LAMA heuristic to solve PDDL problems. The VSCode PDDL extension allows for visualizing the search tree so make sure you understand how the search tree is constructed and how the search algorithm works.

PDDL as a representational language is evolving and new solvers are regularly appearing to allow us to relax the contraints such as determinism, full observability, etc. and apply planning to more realistic problems. The International Planning Competition (IPC) is a biennial event that evaluates the state-of-the-art in automated planning - see IPC 2023 for the latest ICAPS conference and competition.